what problem may have caused the vikings to stop coming to north america

Viking expansion in Europe:

8th century settlement

ninth century settlement

tenth century settlement

11th century settlement

Raids but no settlement

Viking expansion was the historical motion which led Norse explorers, traders and warriors, the latter known in modern scholarship as Vikings, to sail nearly of the North Atlantic, reaching south as far every bit Due north Africa and e as far as Russia, and through the Mediterranean as far every bit Constantinople and the Middle East, acting as looters, traders, colonists and mercenaries. To the due west, Vikings under Leif Erikson, the heir to Erik the Reddish, reached N America and prepare a brusque-lived settlement in present-day L'Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland, Canada. Longer lasting and more than established Norse settlements were formed in Greenland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Russia, Keen U.k., Republic of ireland and Normandy.

It is debated whether the term "Viking" represents all Norse settlers or but those who raided.[1]

Motivation for expansion [edit]

In that location is much debate among historians about what drove the Viking expansion.

Researchers have suggested that Vikings may have originally started sailing and raiding due to a demand to seek out women from foreign lands.[ii] [3] [iv] [v] The concept was expressed in the 11th century by historian Dudo of Saint-Quentin in his semi-imaginary History of The Normans.[6] Rich and powerful Viking men tended to have many wives and concubines, and these polygynous relationships may take led to a shortage of eligible women for the average Viking male. Due to this, the boilerplate Viking human being could have been forced to perform riskier deportment to gain wealth and power to be able to find suitable women.[7] [8] [ix] Viking men would oftentimes buy or capture women and make them into their wives or concubines.[10] [11] Polygynous wedlock increases male-male competition in society because it creates a pool of unmarried men who are willing to engage in risky status-elevating and sex-seeking behaviors.[12] [thirteen] The Register of Ulster states that in 821 the Vikings plundered an Irish hamlet and "carried off a great number of women into captivity".[14]

Another theory is that it was a quest for revenge against continental Europeans for past aggressions confronting the Vikings and related groups,[15] Charlemagne's entrada to force Saxon pagans to convert to Christianity past killing whatsoever who refused to become baptized in item.[sixteen] [17] [18] [19] [20] Those who favor this explanation indicate out that the penetration of Christianity into Scandinavia acquired serious conflict and divided Norway for almost a century.[21] Nonetheless, the first target of Viking raids was not the Frankish Kingdom, only Christian monasteries in England. According to the historian Peter Sawyer, these were raided because they were centers of wealth and their farms well-stocked, not because of any religious reasons.[22]

A depiction of Vikings kidnapping a adult female. Viking men often kidnapped strange women for marriage or concubinage from lands that they had pillaged. Illustrated by French painter Évariste Vital Luminais in the 19th century.

A different idea is that the Viking population had exceeded the agronomical potential of their homeland. This may have been truthful of western Kingdom of norway, where there were few reserves of country, just it is unlikely that the rest of Scandinavia was experiencing dearth.[23]

Alternatively, some scholars advise that the Viking expansion was driven by a youth bulge effect: Considering the eldest son of a family customarily inherited the family'south entire estate, younger sons had to seek their fortune by emigrating or engaging in raids. Peter Sawyer suggests that most Vikings emigrated due to the attractiveness of owning more land rather than the necessity of having it.[24]

However, no rise in population, youth bulge, or decline in agricultural production during this period has been definitively demonstrated. Nor is information technology clear why such pressures would have prompted expansion overseas rather than into the vast, uncultivated forest areas in the interior of the Scandinavian Peninsula, although peradventure emigration or bounding main raids may have been easier or more profitable than clearing large areas of wood for subcontract and pasture in a region with a limited growing season.

It is also possible that a decline in the profitability of old merchandise routes drove the Vikings to seek out new, more profitable ones. Trade betwixt western Europe and the residuum of Eurasia may accept suffered afterward the Roman Empire lost its western provinces in the 5th century, and the expansion of Islam in the seventh century may accept reduced trade opportunities within western Europe by redirecting resource along the Silk Road.[ citation needed ] Trade in the Mediterranean was at its lowest level in history when the Vikings began their expansion.[ citation needed ] The Viking expansion opened new merchandise routes in Arab and Frankish lands, and took control of trade markets previously dominated by the Frisians after the Franks destroyed the Western frisian fleet.[ citation needed ]

Ane of the primary aims of the Viking expansion throughout Europe was to acquire and merchandise silver.[25] [26] Bergen and Dublin are still of import centres of silverish making.[27] [28] An example of a drove of Viking-age silvery for trading purposes is the Galloway Hoard.[29]

Settlement demographics [edit]

Viking settlements in Republic of ireland and Great U.k. are idea to have been primarily male enterprises; however, some graves show nearly equal male person/female distribution. Disagreement is partly due to method of classification; previous archaeology oftentimes guessed biological sexual practice from burial artifacts, whereas modern archaeology may use osteology to find biological sexual activity, and isotope analysis to find origin (Dna sampling is commonly not possible).[thirty] [31] The males buried during that period in a cemetery on the Isle of Human being had mainly names of Norse origin, while the females there had names of indigenous origin. Irish and British women are mentioned in old texts on the founding of Iceland, indicating that the Viking explorers were accompanied there by women from the British Isles who either came forth voluntarily or were taken forth by forcefulness. Genetic studies of the population in the Western Isles and Isle of Skye also prove that Viking settlements were established mainly by male Vikings who mated with women from the local populations of those places.[ citation needed ]

However, non all Viking settlements were primarily male person. Genetic studies of the Shetland population advise that family units consisting of Viking women every bit well equally men were the norm amongst the migrants to these areas.[32]

This may be considering areas like the Shetland Islands, existence closer to Scandinavia, were more suitable targets for family unit migrations, while borderland settlements further north and due west were more suitable for groups of unattached male colonizers.[33]

British Isles [edit]

England [edit]

Map of England in 878, depicting the Danelaw territory

King Canute's territories 1014–1035. (Note that the Norwegian lands of Jemtland, Herjedalen, Idre and Særna are non included in this map).

During the reign of King Beorhtric of Wessex (786–802) three ships of "Northmen" landed at Portland Bay in Dorset.[34] The local reeve mistook the Vikings for merchants and directed them to the nearby royal estate, just the visitors killed him and his men. On 8 June 793 "the ravages of heathen men miserably desecrated God'southward church building on Lindisfarne, with plunder and slaughter".[35] Co-ordinate to the 12th-century Anglo-Norman chronicler Symeon of Durham, the raiders killed the resident monks or threw them into the sea to drown or carried them away every bit slaves – along with some of the church building treasures.[36] In 875, after enduring eight decades of repeated Viking raids, the monks fled Lindisfarne, conveying the relics of Saint Cuthbert with them.[37]

In 794, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a pocket-sized Viking fleet attacked a rich monastery at Jarrow.[38] The Vikings met with stronger resistance than they had expected: their leaders were killed. The raiders escaped, only to have their ships beached at Tynemouth and the crews killed by locals.[39] [40] This represented one of the last raids on England for almost twoscore years. The Vikings focused instead on Republic of ireland and Scotland.

In 865, a group of hitherto uncoordinated bands of predominantly Danish Vikings joined to form a large army and landed in East Anglia.[41] The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle described this force as the mycel hæþen hither (Great Heathen Regular army) and went on to say that it was led by Ivar the Boneless and Halfdan Ragnarsson.[42] [43] [44] [45] The ground forces crossed the Midlands into Northumbria and captured York (Jorvik).[41] In 871, the Bang-up Pagan Army was reinforced past some other Danish force known every bit the Great Summer Regular army led by Guthrum. In 875, the Great Heathen Regular army carve up into 2 bands, with Guthrum leading one back to Wessex, and Halfdan taking his followers north.[46] [47] Then in 876, Halfdan shared out Northumbrian land south of the Tees amongst his men, who "ploughed the land and supported themselves", founding the territory afterward known equally the Danelaw. [a] [47]

Most of the English kingdoms, being in turmoil, could not stand against the Vikings, only King Alfred of Wessex defeated Guthrum'southward army at the Battle of Edington in 878. In that location followed the Treaty of Wedmore the aforementioned twelvemonth[51] [52] and the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum in 886.[53] [54] These treaties formalised the boundaries of the English language kingdoms and the Viking Danelaw territory, with provisions for peaceful relations betwixt the English and the Vikings. Despite these treaties, conflict continued on and off. Yet, Alfred and his successors eventually drove back the Viking borderland and retook York.[55]

A new moving ridge of Vikings appeared in England in 947, when Erik Bloodaxe captured York.[56] The Viking presence continued through the reign of the Danish prince Cnut the Great (reigned as King of England: 1016–1035), after which a series of inheritance arguments weakened the hold on power of Cnut'south heirs.

When King Edward the Confessor died in 1066, the Norwegian king Harald Hardrada challenged his successor as King of England, Harold Godwinson. Hardrada was killed, and his Norwegian army defeated, by Harold Godwinson on 25 September 1066 at the Battle of Stamford Bridge.[57] Harold Godwinson himself died when the Norman William the Conquistador defeated the English ground forces at the Battle of Hastings in October 1066. William was crowned rex of England on 25 December 1066; however, it was several years earlier he was able to bring the kingdom under his complete control.[58] In 1070 the Danish king Sweyn Estridsson sailed up the Humber with an army in support of Edgar the Ætheling, the last surviving male member of the English royal family unit. All the same, after capturing York, Sweyn accepted a payment from William to desert Edgar.[58] [59] Five years afterward one of Sweyn's sons set canvass for England to back up another English language rebellion, but information technology had been crushed before the expedition arrived, so they settled for plundering the metropolis of York and the surrounding area earlier returning home.[58]

In 1085 Sweyn's son, now Canute 4 of Denmark, planned a major invasion of England but the assembled fleet never sailed. No further serious Danish invasions of England occurred after this.[58] Although, some raiding occurred during the troubles of Stephen's reign, when King Eystein II of Norway took advantage of the civil war to plunder the e declension of England, sacking Hartlepool and Whitby in 1152, as well as raiding the Yorkshire coast. Notwithstanding, the intention was raids not conquest, and their conclusion marked the end of the Viking Historic period in England.[lx] [61]

Scotland [edit]

The monastery at Iona on the west coast was first raided in 794, and had to exist abandoned some fifty years later afterwards several devastating attacks.[62] While at that place are few records from the earliest menses, it is believed that Scandinavian presence in Scotland increased in the 830s.[ commendation needed ]

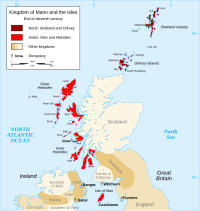

The isles to the n and westward of Scotland were heavily colonised by Norwegian Vikings. Shetland, Orkney and the Hebrides came under Norse control, sometimes as fiefs under the King of Kingdom of norway, and at other times as divide entities nether variously the Kings of the Isles, the Earldom of Orkney and the later on Kings of Isle of mann and the Isles. Shetland and Orkney were the concluding of these to be incorporated into Scotland in as late as 1468.

Wales [edit]

Viking colonies were non a feature of Wales every bit much as the other nations of the British Isles. This has traditionally been attributed to the powerful unified forces of the contemporary kings, specially Rhodri the Great. As such, the Vikings were unable to establish whatever states or areas of control in Wales and were largely limited to raids and trading.

The Danish are recorded raiding Anglesey in 854. However, Welsh record state that two years later, Rhodri the Smashing would win a notable victory, killing the Danish leader, Male monarch Gorm. 2 farther victories by Rhodri are recorded in the Brut y Tywysogion for 872. The outset battle was at a place named as Bangolau or Bann Guolou or Bannoleu,[63] [64] [65] where the Vikings in Anglesey were again defeated "in a hard battle".[63] In the second battle at Manegid or Enegyd, the records state that the remaining Vikings "were destroyed".[63] [66]

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle of 893, records Viking armies being pursued by a combined force of Westward Saxons and n Welsh along the River Severn.[67] This combined ground forces eventually overtook the Vikings before defeating them at the Battle of Buttington.[68]

Impact on English names in Wales [edit]

The Normans in Wales shared both the linguistic communication and history of the Vikings in Wales. As such, it was frequently the Viking names that were favoured past the Cambro-Normans, and passed into Heart English. This impact can be seen today where many coastal names in Wales accept an English proper name derived from the Vikings and unrelated to the original Welsh name.[69]

The modern English name Anglesey (Welsh: Ynys Môn) is of Scandinavian origin, as are a number of the island's most prominent coastal features. The English language names for Caldey Island (Welsh: Ynys Bŷr), Flat Holm (Welsh: Ynys Echni) and Grassholm (Welsh: Ynys Gwales) are also those of the Viking raiders.[70] Wales' 2nd largest city, Swansea (Welsh: Abertawe) takes its English name from a Viking trading post founded by Sweyn Forkbeard. The original name, Former Norse: Sveinsey translates as Sweyn's island or Sweyn's inlet. Worm'south Caput (Welsh: Ynys Weryn) is derived from Onetime Norse: ormr, the give-and-take for serpent or dragon, from the Vikings' tradition that the serpent-shaped island was a sleeping dragon.[71]

Cornwall [edit]

The Anglo-Saxon Relate reported that pagan men (the Danes) raided Charmouth, Dorset in 833 AD, and then in 997 Ad they destroyed the Dartmoor town of Lydford, and from 1001 AD to 1003 Advertising they occupied the old Roman city of Exeter.[72]

The Cornish were subjugated by Rex Æthelstan, of England, in 936 and the edge finally set at the River Tamar. However, the Cornish remained semi-autonomous until their annexation into England after the Norman Conquest.[73]

Ireland [edit]

Areas of Norse influence in 10th century Ireland

In 795, small bands of Vikings began plundering monastic settlements along the coast of Gaelic Ireland. The Register of Ulster state that in 821 the Vikings plundered Howth and "carried off a groovy number of women into captivity".[74] From 840 the Vikings began building fortified encampments, longphorts, on the declension and overwintering in Ireland. The first were at Dublin and Linn Duachaill.[75] Their attacks became bigger and reached farther inland, striking larger monastic settlements such as Armagh, Clonmacnoise, Glendalough, Kells and Kildare, and also plundering the ancient tombs of Brú na Bóinne.[76] Viking chief Thorgest is said to have raided the whole midlands of Ireland until he was killed by Máel Sechnaill I in 845.

In 853, Viking leader Amlaíb (Olaf) became the first king of Dublin. He ruled along with his brothers Ímar (possibly Ivar the Boneless) and Auisle.[77] Over the following decades, at that place was regular warfare between the Vikings and the Irish, and between 2 groups of Vikings: the Dubgaill and Finngaill (night and fair foreigners). The Vikings also briefly allied with various Irish kings against their rivals. In 866, Áed Findliath burnt all Viking longphorts in the north, and they never managed to institute permanent settlements in that region.[78] The Vikings were driven from Dublin in 902.[79]

They returned in 914, led by the Uí Ímair (House of Ivar).[80] During the next eight years, the Vikings won decisive battles against the Irish gaelic, regained control of Dublin, and founded settlements at Waterford, Wexford, Cork and Limerick, which became Ireland's first large towns. They were important trading hubs, and Viking Dublin was the biggest slave port in western Europe.[81]

These Viking territories became part of the patchwork of kingdoms in Ireland. Vikings intermarried with the Irish gaelic and adopted elements of Irish culture, becoming the Norse-Gaels. Some Viking kings of Dublin also ruled the kingdom of the Isles and York; such as Sitric Cáech, Gofraid ua Ímair, Olaf Guthfrithson and Olaf Cuaran. Sitric Silkbeard was "a patron of the arts, a benefactor of the church, and an economic innovator" who established Ireland's beginning mint, in Dublin.[82]

In 980, Máel Sechnaill Mór defeated the Dublin Vikings and forced them into submission.[83] Over the following thirty years, Brian Boru subdued the Viking territories and fabricated himself Loftier Rex of Ireland. The Dublin Vikings, together with Leinster, twice rebelled against him, but they were defeated in the battles of Glenmama (999) and Clontarf (1014). Afterwards the battle of Clontarf, the Dublin Vikings could no longer "single-handedly threaten the power of the about powerful kings of Republic of ireland".[84] Brian'south rise to power and disharmonize with the Vikings is chronicled in Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib ("The State of war of the Irish with the Foreigners").

European mainland [edit]

Statue of Rollo, Duke of Normandy

Normandy [edit]

The name of Normandy itself denotes its Viking origin, from "Northmannia" or State of The Norsemen.

The Viking presence in Normandy began with raids into the territory of the Frankish Empire, from the heart of 9th century. Viking raids extended deep into the Frankish territory, and included the sacking of many prominent towns such as Rouen, Paris and the abbey at Jumièges. The inability of the Frankish king Charles the Baldheaded, and subsequently Charles the Simple, to foreclose these Viking incursions forced them to offer vast payments of argent and gilt to preclude whatsoever further pillage. These pay-offs were short lived and the Danish raiders would always render for more.

The Duchy of Normandy was created for the Viking leader Rollo after he had besieged Paris. In 911, Rollo entered vassalage to the king of the West Franks Charles the Simple through the Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte. This treaty fabricated of Rollo the first Norman Count of Rouen. In addition, Rollo was to be baptized and ally Gisele, the illegitimate daughter of Charles. In substitution for his homage and fealty, Rollo legally gained the territory which he and his Viking allies had previously conquered.

The descendants of Rollo and his followers adopted the local Gallo-Romance languages and intermarried with the surface area's original inhabitants. They became the Normans – a Norman French-speaking mixture of Scandinavians and indigenous Franks and Gauls. The language of Normandy heavily reflected the Danish influence, as many words (especially ones pertaining to seafaring) were borrowed from Old Norse[85] or Old Danish.[86] More than the linguistic communication itself, the Norman toponymy retains a stiff Nordic influence. Yet, only a few archaeological traces have been plant: swords dredged out of the Seine river between its estuary and Rouen, the tomb of a female Viking at Pîtres, the two Thor's hammers at Saint-Pierre-de-Varengeville and Sahurs[87] and more recently the hoard of Viking coins at Saint-Pierre-des-Fleurs.[88]

Rollo's descendant William, Duke of Normandy (the Conquistador) became King of England later on he defeated Harold Godwinson and his army at the Battle of Hastings in October 1066. Every bit king of England, he retained the fiefdom of Normandy for himself and his descendants. The kings of England made claim to Normandy, as well as their other possessions in French republic, which led to various disputes with the French. This culminated in the French confiscation of Gascony that precipitated what became known as the Hundred Years' War, in 1337.[89]

Due west Francia and Middle Francia [edit]

West Francia and Middle Francia suffered more severely than East Francia during the Viking raids of the 9th century. The reign of Charles the Baldheaded coincided with some of the worst of these raids, though he did take action past the Edict of Pistres of 864 to secure a continuing ground forces of cavalry under royal control to be chosen upon at all times when necessary to fend off the invaders. He also ordered the edifice of fortified bridges to prevent inland raids.

Notwithstanding, the Bretons allied with the Vikings and Robert, the margrave of Neustria, (a march created for defence against the Vikings sailing upwardly the Loire), and Ranulf of Aquitaine died in the Battle of Brissarthe in 865. The Vikings also took advantage of the civil wars which ravaged the Duchy of Aquitaine in the early years of Charles' reign. In the 840s, Pepin Two called in the Vikings to help him against Charles and they settled at the rima oris of the Garonne as they did by the Loire. Two dukes of Gascony, Seguin 2 and William I, died defending Bordeaux from Viking assaults. A afterwards knuckles, Sancho Mitarra, fifty-fifty settled some at the mouth of the Adour about Bayonne in an human action[ which? ] presaging that of Charles the Simple and the Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte past which the Vikings were settled in Rouen, creating Normandy as a bulwark against other Vikings.

In the 9th and 10th centuries, the Vikings raided the largely defenceless Frisian and Frankish towns lying on the declension and along the rivers of the Depression Countries. Although Vikings never settled in large numbers in those areas, they did ready up long-term bases and were even acknowledged as lords in a few cases. They fix bases in Saint-Florent-le-Vieil at the oral cavity of the Loire, in Taillebourg on the mid Charente, also around Bayonne on the banks of the Adour, in Noirmoutier and apparently on the River Seine (Rouen) in what would become Normandy.

Antwerp was raided in 836. Later there were raids of Ghent, Kortrijk, Tournai, Leuven and the areas around the Meuse river, the Rhine, the Rupel river and the tributaries of those rivers. Raids were conducted from bases established in Asselt, Walcheren, Wieringen and Elterberg (or Eltenberg, a small-scale colina well-nigh Elten). In Dutch and Western frisian historical tradition, the trading centre of Dorestad declined after Viking raids from 834 to 863; however, since no convincing Viking archaeological evidence has been found at the site (as of 2007[update]), doubts about this have grown in contempo years.

One of the more important Viking families in the Low Countries was that of Rorik of Dorestad (based in Wieringen) and his brother Harald (based in Walcheren). Around 850, Lothair I acknowledged Rorik as ruler of most of Friesland. Once more in 870, Rorik was received by Charles the Bald in Nijmegen, to whom he became a vassal. Viking raids continued during this menstruum. Harald's son Rodulf and his men were killed by the people of Oostergo in 873. Rorik died sometime before 882.

Buried Viking treasures consisting mainly of silver have been institute in the Depression Countries. Two such treasures have been found in Wieringen. A large treasure found in Wieringen in 1996 dates from around 850 and is idea peradventure to have been connected to Rorik. The burying of such a valuable treasure is seen as an indication that there was a permanent settlement in Wieringen.[90]

Effectually 879, Godfrid arrived in Western frisian lands equally the head of a large forcefulness that terrorised the Low Countries. Using Ghent equally his base, they ravaged Ghent, Maastricht, Liège, Stavelot, Prüm, Cologne, and Koblenz. Controlling nigh of Frisia between 882 and his death in 885, Godfrid became known to history as Godfrid, Duke of Frisia. His lordship over Frisia was acknowledged by Charles the Fat, to whom he became a vassal. In the siege of Asselt in 882, the Franks sieged a Viking camp at Asselt in Frisia. Although the Vikings were non forced by artillery to abandon their campsite, they were compelled to come up to terms in which their leader, Godfrid, was converted to Christianity. Godfrid was assassinated in 885, after which Gerolf of Holland assumed lordship and Viking rule of Frisia came to an terminate.

Viking raids of the Low Countries continued for over a century. Remains of Viking attacks dating from 880 to 890 take been found in Zutphen and Deventer. The concluding attacks took identify in Tiel in 1006 and Utrecht in 1007.

Iberian Peninsula [edit]

Compared with the rest of Western Europe, the Iberian Peninsula seems to have been little affected by Viking activity, either in the Christian north or the Muslim south.[92] In some of their raids on Iberia, the Vikings were crushed either by the Kingdom of Asturias or the Emirate armies.[93]

Our cognition of Vikings in Iberia is mainly based on written accounts, many of which are much later than the events they purport to depict, and often likewise ambiguous about the origins or ethnicity of the raiders they mention.[94] A little possible archaeological prove has come to light,[95] just research in this area is ongoing.[96] Viking activity in the Iberian peninsula seems to accept begun effectually the mid-9th century as an extension of their raids on and establishment of bases in Frankia in the before ninth century, just although Vikings may have over-wintered there, at that place is as yet no evidence for trading or settlement.[97]

The nearly prominent and probably nigh significant event was a raid in 844, when Vikings entered the Garonne and attacked Galicia and Asturias. When the Vikings attacked La Coruña they were met by the army of King Ramiro I and were heavily defeated. Many of the Vikings' casualties were caused by the Galicians' ballistas – powerful torsion-powered projectile weapons that looked rather like giant crossbows.[98] Seventy of the Vikings' longships were captured on the embankment and burned.[98]

They and then proceeded south, raiding Lisbon and Seville. This Viking raid on Seville seems to accept constituted a significant attack.[99]

The period from 859 to 861 saw another spate of Viking raids, apparently past a single grouping. Despite some elaborate tales in late sources, piffling is known for sure about these attacks. Later on raids on both northern Iberia and Al-Andalus, ane of which in 859 resulted in the capture and exorbitant ransom of rex García Íñiguez of Pamplona,[100] the Vikings seem also to have raided other Mediterranean targets – maybe but non certainly including Italia, Alexandria, and Constantinople−and perhaps overwintering in Francia.[101]

Bear witness for Viking activity in Iberia vanishes after the 860s, until the 960s–70s, when a range of sources including Dudo of Saint-Quentin, Ibn Ḥayyān, and Ibn Idhārī, along with a number of charters from Christian Iberia, while individually unreliable, together afford convincing prove for Viking raids on Iberia in the 960s and 970s.[102]

Tenth- or eleventh-century fragments of mouse bone found in Madeira, along with mitocondrial Dna of Madeiran mice, suggests that Vikings also came to Madeira (bringing mice with them), long before the island was colonised past Portugal.[95]

Quite all-encompassing evidence for minor Viking raids in Iberia continues for the early eleventh century in later narratives (including some Icelandic sagas) and in northern Iberian charters. As the Viking Age drew to a close, Scandinavians and Normans continued to take opportunities to visit and raid Iberia while on their way to the Holy Land for pilgrimage or cause, or in connection with Norman conquests in the Mediterranean. Key examples in the saga literature are Sigurðr Jórsalafari (king of Norway 1103–1130) and Røgnvaldr kali Kolsson (d. 1158).[103]

Italy and Sicily [edit]

Around 860, Ermentarius of Noirmoutier and the Annals of St-Bertin provide contemporary evidence for Vikings based in Frankia proceeding to Iberia and thence to Italia.[104]

Three or four eleventh-century Swedish Runestones mention Italia, memorialising warriors who died in 'Langbarðaland', the Old Norse proper name for southern Italy (Longobardia). It seems clear that rather than beingness Normans, these men were Varangian mercenaries fighting for Byzantium.[105] Varangians may first have been deployed as mercenaries in Italy against the Arabs every bit early on equally 936.[106]

Later, several Anglo-Danish and Norwegian nobles participated in the Norman conquest of southern Italian republic. Harald Hardrada, who later became king of Norway, seems to take been involved in the Norman conquest of Sicily between 1038 and 1040,[105] nether William de Hauteville, who won his nickname Iron Arm by defeating the emir of Syracuse in single combat, and a Lombard contingent, led by Arduin.[107] [108] Edgar the Ætheling, who left England in 1086, went at that place,[109] Jarl Erling Skakke won his nickname afterwards a boxing against Arabs in Sicily.[110] On the other manus, many Anglo-Danish rebels fleeing William the Conqueror, joined the Byzantines in their struggle against Robert Guiscard, knuckles of Apulia, in Southern Italia.[111]

Islamic Levant [edit]

The well-known Harald Hardrada would also serve the Byzantine emperor in Palestine also equally raiding N Africa, the Middle East every bit far east equally Armenia, and the island of Sicily in the 11th century, every bit recounted in his saga in Snorri Sturluson'due south Heimskringla.[112]

Evidence for Norse ventures into Arabia and Key Asia can exist plant in runestones erected in Scandinavia by the relatives of fallen Viking adventurers. Several of these refer to men who died in "Serkland".[113] [114]

Meanwhile, in the Eastern Mediterranean the Norse (referred to equally Rus') were viewed more equally "merchant-warriors" who were primarily associated with trade and business.[115] Indeed, one of the merely detailed accounts of a Viking burial come from Ibn-Fadlan'south account.[116] At times this trading relationship would break down into violence – Rus' armadas raided in the Caspian on at least three occasions, in 910, 912 and 943.[115]

Eastern Europe [edit]

In Athens, Greece, Swedish Vikings wrote a runic inscription on the Piraeus Lion

The Vikings settled coastal areas forth the Baltic Sea, and forth inland rivers in Russian territories such as Staraya Ladoga, Novgorod and along major waterways to the Byzantine Empire.

The Varangians or Varyags (Russian, Ukrainian: Варяги, Varyagi) sometimes referred to as Variagians were Scandinavians who migrated eastwards and southwards through what is at present Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine mainly in the 9th and 10th centuries. Engaging in trade, colonization, piracy and mercenary activities, they roamed the river systems and portages of Garðaríki, reaching and settling at the Caspian Sea and in Constantinople.[117]

The real involvement of the Varangians is said to take come up afterwards they were asked by the Slavic tribes of the region to come up and establish social club, as those tribes were in constant warfare among each other ("Our country is rich and immense, but it is hire by disorder. Come and govern u.s.a. and reign over united states."[118]). The tribes were united and ruled under the leadership of Rurik, a leader of a group of Varangians. Rurik had successfully been able to establish a set of trading towns and posts forth the Volga and Dnieper Rivers, which were perfect for trade with the Byzantine Empire. Rurik's successors were able to conquer and unite the towns forth the banks of the Volga and Dnieper Rivers, and institute the Rus' Khaganate. Despite the distinction of the Varangians from the local Slavic tribes at the showtime, past the tenth century, the Varangians began to integrate with the local community, and past the end of 12th century, a new people – the Russians, had emerged.

Iran and the Caucasus [edit]

Ingvar the Far-Travelled led expeditions to Islamic republic of iran and the Caucasus between 1036 and 1042. His travels are recorded on the Ingvar runestones.[119]

Around 1036, Varangians appeared near the village of Bashi on the Rioni River, to establish a permanent[ clarification needed ] settlement of Vikings in Georgia. The Georgian Chronicles described them as 3,000 men who had traveled from Scandinavia through present-day Russia, rowing down the Dnieper River and beyond the Black Body of water. King Bagrat IV welcomed them to Georgia and accepted some of them into the Georgian army; several hundred Vikings fought on Bagrat's side at the Battle of Sasireti in 1042.

Due north Atlantic [edit]

Iceland [edit]

Iceland was discovered past Naddodd, one of the first settlers on the Faroe Islands, who was sailing from Norway to the Faroe Islands but got lost and drifted to the east coast of Iceland. Naddoddr named the country Snæland (Snowland). Swedish crewman Garðar Svavarsson also accidentally drifted to the coast of Iceland. He discovered that the country was an island and named it Garðarshólmi (literally Garðar's Islet) and stayed for the winter at Húsavík. The first Scandinavian who deliberately sailed to Garðarshólmi was Flóki Vilgerðarson, as well known as Hrafna-Flóki (Raven-Flóki). Flóki settled for 1 wintertime at Barðaströnd. It was a cold winter, and when he spotted some drift ice in the fjords he gave the island its current proper noun, Ísland (Iceland).

Iceland was first settled around 870.[121] The first permanent settler in Iceland is usually considered to have been a Norwegian chieftain named Ingólfr Arnarson. According to the story, he threw two carved pillars overboard as he neared land, vowing to settle wherever they landed. He and so sailed along the coast until the pillars were found in the southwestern peninsula, at present known every bit Reykjanesskagi. In that location he settled with his family around 874, in a place he named Reykjavík (Bay of Smokes) due to the geothermal steam rise from the earth. It is recognized, however, that Ingólfur Arnarson may not have been the first one to settle permanently in Republic of iceland – that may accept been Náttfari, a slave of Garðar Svavarsson who stayed behind when his master returned to Scandinavia.

Greenland [edit]

In the year 985, Erik the Ruddy was believed to have discovered Greenland afterwards beingness exiled from Republic of iceland for murder in 982. Three years later on in 986, Erik the Red returned with xiv surviving ships (as 25 set out on the expedition). Two areas forth Greenland's southwest coast were colonized past Norse settlers, including Erik the Red, effectually 986.[122] [123] The land was at best marginal for Norse pastoral farming. The settlers arrived during a warm phase, when curt-flavor crops such as rye and barley could be grown. Sheep and hardy cattle were also raised for food, wool, and hides. Their primary export was walrus ivory, which was traded for atomic number 26 and other goods which could not be produced locally. Greenland became a dependency of the king of Kingdom of norway in 1261. During the 13th century, the population may accept reached every bit high as v,000, divided between the two master settlements of Eystribygð (Eastern Settlement) and Vestribygð (Western Settlement). The arrangement of these settlements revolved mainly around religion, and they consisted of effectually 250 farms, which were split into approximately xiv communities that were centered around fourteen churches,[124] ane of which was a cathedral at Garðar. The Catholic diocese of Greenland was subject to the archdiocese of Nidaros. Yet, many bishops chose to exercise this role from distant. As the years wore on, the climate shifted (see Little Ice Age). In 1379, the northernmost settlement was attacked by the Skræling (Norse give-and-take for Inuit).[125] Crops failed and trade declined. The Greenland colony gradually faded away. By 1450, information technology had lost contact with Norway and Republic of iceland and disappeared from all but a few Scandinavian legends.[126]

N America [edit]

A Norwegian send's captain named Bjarni Herjólfsson beginning came beyond a office of the Northward American continent ca. 985 when he was diddled off course sailing to Greenland from Iceland. Subsequent expeditions from Greenland (some led past Leif Erikson) explored the areas to the w, seeking big timbers for edifice in particular (Greenland had only small trees and brush). Regular activeness from Greenland extended to Ellesmere Island, Skraeling Island and Ruin Island for hunting and trading with Inuit groups. A brusk-lived settlement was established at L'Anse aux Meadows, located on the Groovy Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland, Canada. Woods from timber-framed buildings in the settlement was dated by a solar storm in the year 993 which caused a spike in carbon fourteen in the dendrochronological layer for the year. Tree rings were counted from that yr on three separate logs from the settlement, and all three were found to have been felled in the year 1021, indicating that the settlement was occupied at that date.[127]

There is also evidence for Viking contact with Native Americans.[128] The Vikings referred to them as the Skræling ("barbarians" or "puny, weaklings"). Fighting betwixt the Natives and the Vikings did take place with the natives having the advanced weaponry of bows and arrows. However trade past castling did also accept place betwixt them. However, the conflict betwixt these two groups led to the Vikings' eventual evacuation of the area.

The Greenlanders called the new-plant territory Vinland. It is unclear whether Vinland referred to in the traditionally thinking as Vínland (wine-land) or more recently as Vinland (meadow- or pasture-land). In any example, without any official backing, attempts at colonization by the Norse proved failures. There were simply too many natives for the Greenlanders to conquer or withstand and they withdrew to Greenland.

Svalbard [edit]

Vikings may have discovered Svalbard every bit early as the 12th century. Traditional Norse accounts exist of a country known as Svalbarð – literally "cold shores". This state might also take been January Mayen, or a function of eastern Greenland. The Dutchman Willem Barents made the first indisputable discovery of Svalbard in 1596.

Genetic evidence and implications [edit]

Studies of genetic diversity have provided scientific confirmation to accompany archaeological evidence of Viking expansion. They additionally bespeak patterns of ancestry, imply new migrations, and show the actual flow of individuals between disparate regions. However, attempts to decide historical population genetics are complicated by subsequent migrations and demographic fluctuations. In particular, the rapid migrations of the 20th century have made it difficult to assess what prior genetic states were.

Genetic evidence contradicts the common perception that Vikings were primarily pillagers and raiders. A news article by Roger Highfield summarizes recent enquiry and concludes that, equally both male and female person genetic markers are present, the evidence is indicative of colonization instead of raiding and occupying.[129] However, this is also disputed by unequal ratios of male person and female person haplotypes (see below) which bespeak that more men settled than women, an element of a raiding or occupying population.

Mitochondrial and Y-chromosome haplotypes [edit]

Y-chromosome haplotypes serve as markers of paternal lineage much the aforementioned as mDNA represents the maternal lineage. Together, these two methods provide an option for tracing dorsum a people'southward genetic history and charting the historical migrations of both males and females.

Often considered the purest remnants of aboriginal Nordic genetics, Icelanders trace 75% to 80% of their patrilineal beginnings to Scandinavia and xx% to 25% to Scotland and Republic of ireland.[130] [131] On the maternal side, only 37% is from Scandinavia and the remaining 63% is mostly Scottish and Irish.[131] [132] Iceland also holds one of the more well-documented lineage records which, in many cases, go dorsum 15 generations and at least 300 years. These are accompanied past one of the larger genetic records that have been collected by deCODE genetics. Together, these two records allow for a generally reliable view of historical Scandinavian genetic structure although the genetics of Iceland are influenced past Norse-British migration besides as that direct from Scandinavia.[ commendation needed ]

Mutual Y-haplogroups [edit]

Haplogroup I-M253, too known as haplogroup I1, is the most common haplotype amid Scandinavian males. It is present in 35% of males in Kingdom of norway, Denmark and Sweden; xl% of males inside Western Finland.[133] It is besides prominent on the Baltic and North Ocean coasts, but decreases further south.[ citation needed ]

Haplogroup R1b is another very common haplotype in all of Western Europe. However, information technology is not distinctly linked to Vikings or their expansion. In that location are indications that a mutant strand, R-L165, may accept been carried to Great britain by the Vikings,[134] but the topic is currently inconclusive.

C1 [edit]

The mitochondrial C1 haplotype is primarily an Eastern asia-American haplotype that adult just prior to migration across the Bering body of water.[135] [136] This maternal haplotype, notwithstanding, was plant in several Icelandic samples.[130] While originally considered to exist a 20th-century immigrant,[130] a more complete assay has shown that this haplotype has been present in Iceland for at to the lowest degree 300 years and is singled-out from other C1 lineages.[137] This bear witness indicates a likely genetic exchange back and along between Iceland, Greenland, and Vinland.[ citation needed ]

Surname histories and the Y-haplotype [edit]

In that location is show suggesting Y-haplotypes may be combined with surname histories to better stand for historical populations and prevent recent migrations from obscuring the historical record.[48]

Cys282Tyr [edit]

Cys282Tyr (or C282Y) is a mutation in the HFE cistron that has been linked to near cases of hereditary hemochromatosis. Genetic techniques indicate that this mutation occurred roughly 60–70 generations agone or betwixt 600 and 800 CE, assuming a generation length of 20 years.[138] [139] The regional distribution of this mutation among European populations indicates that information technology originated in Southern Scandinavia and spread with Viking expansion.[140] Due to the timing of the mutation and subsequent population movements, C282Y is very prominent in Great Britain, Normandy, and Southern Scandinavia although C282Y has been found in almost every population that has been in contact with the Vikings.[140]

Run into besides [edit]

- The Exploration Museum

- Salme ships

Explanatory notes [edit]

- ^ Not all the Norse arriving in Ireland and Smashing United kingdom came as raiders. Many arrived with families and livestock, often in the wake of the capture of territory by their forces. The populations then merged over fourth dimension by intermarriage into the Anglo-Saxon population of these areas.[48] [49] Many words in the English language come from onetime Scandinavian languages.[50]

References [edit]

- ^ Graham-Campbell and Batey 1998. p. 3.

- ^ Hrala, Josh. "Vikings Might Have Started Raiding Considering There Was a Shortage of Unmarried Women". ScienceAlert. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 2019-07-xix .

- ^ Choi, Charles Q. (viii Nov 2016). "The Real Reason for Viking Raids: Shortage of Eligible Women?". Alive Science. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 2019-07-21 .

- ^ "Sex Slaves – The Dirty Secret Behind The Founding Of Iceland". All That's Interesting. 2018-01-16. Archived from the original on 22 July 2019. Retrieved 2019-07-22 .

- ^ "Kinder, Gentler Vikings? Not Co-ordinate to Their Slaves". National Geographic News. 2015-12-28. Archived from the original on two Baronial 2019. Retrieved 2019-08-02 .

- ^ David R. Wyatt (2009). Slaves and Warriors in Medieval Uk and Ireland: 800–1200. Brill. p. 124. ISBN978-90-04-17533-4.

- ^ Viegas, Jennifer (2008-09-17). "Viking Age triggered by shortage of wives?". msnbc.com. Archived from the original on 23 July 2019. Retrieved 2019-07-21 .

- ^ Knapton, Sarah (2016-11-05). "Viking raiders were only trying to win their future wives' hearts". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 1 August 2019. Retrieved 2019-08-01 .

- ^ "New Viking Study Points to "Beloved and Wedlock" as the Principal Reason for their Raids". The Vintage News. 2018-x-22. Archived from the original on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 2019-08-02 .

- ^ Karras, Ruth Mazo (1990). "Concubinage and Slavery in the Viking Age". Scandinavian Studies. 62 (2): 141–162. ISSN 0036-5637. JSTOR 40919117.

- ^ Poser, Charles 1000. (1994). "The dissemination of multiple sclerosis: A Viking saga? A historical essay". Annals of Neurology. 36 (S2): S231–S243. doi:ten.1002/ana.410360810. ISSN 1531-8249. PMID 7998792. S2CID 36410898.

- ^ Raffield, Ben; Price, Neil; Collard, Mark (2017-05-01). "Male-biased operational sex ratios and the Viking phenomenon: an evolutionary anthropological perspective on Late Atomic number 26 Age Scandinavian raiding". Evolution and Human being Beliefs. 38 (3): 315–24. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2016.10.013. ISSN 1090-5138.

- ^ "Vikings may take first taken to seas to find women, slaves". Science | AAAS. 2016-04-13. Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 2019-07-19 .

- ^ Andrea Dolfini; Rachel J. Crellin; Christian Horn; Marion Uckelmann (2018). Prehistoric Warfare and Violence: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. Springer. p. 349. ISBN978-3-319-78828-nine.

- ^ Einhards Jahrbücher, Anno 808, p. 115.

- ^ Bruno Dumézil, primary of Conference at Paris X-Nanterre, Normalien, aggregated history, writer of Conversion and freedom in the barbarian kingdoms, fifth – 8th centuries (Fayard, 2005)

- ^ "Franques Royal Annals" cited in Peter Sawyer, The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings, 2001, p. xx.

- ^ Dictionnaire d'histoire de France – Perrin – Alain Decaux and André Castelot. 1981. pp. 184–85 ISBN 2-7242-3080-ix.

- ^ Les vikings : Histoire, mythes, dictionnaire R. Boyer, Robert Laffont, 2008, p. 96 ISBN 978-2-221-10631-0

- ^ François-Xavier Dillmann, Viking civilisation and culture. A bibliography of French-language, Caen, Centre for inquiry on the countries of the North and Northwest, University of Caen, 1975, p. nineteen, and Les Vikings – the Scandinavian and European 800–1200, 22nd exhibition of art from the Council of Europe, 1992, p. 26.

- ^ History of the Kings of Norway past Snorri Sturlusson translated by Professor of History François-Xavier Dillmann, Gallimard ISBN two-07-073211-8 pp. 15–sixteen, 18, 24, 33, 34, 38.

- ^ Sawyer, Peter (2001). The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings. Oxford: OUP. p. 96. ISBN978-0-19-285434-6.

- ^ Sawyer, Peter (2001). The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings. Oxford: OUP. p. three. ISBN978-0-19-285434-6.

- ^ Sawyer, Peter (1997). The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings. Oxford. p. 3.

- ^ "Datahub of ERC funded projects". erc.easme-web.eu . Retrieved 2021-10-19 .

- ^ "Silvery and the Origins of the Viking Age: An ERC projection". Retrieved 2021-x-xix – via sites.google.com.

- ^ "Viking Ireland | Archeology". National Museum of Ireland . Retrieved 2021-ten-19 .

- ^ "..The Silver Treasure | KODE..." kodebergen.no . Retrieved 2021-10-19 .

- ^ History, Scottish; read, Archaeology fifteen min. "The Galloway Hoard in the context of the Viking-historic period". National Museums Scotland. Retrieved 2021-10-19 .

- ^ Shane McLeod. "Warriors and women: the sex ratio of Norse migrants to eastern England upwards to 900 Ad" xviii Jul 2011. Early Medieval Europe, Volume nineteen, Issue 3, pp. 332–53, Baronial 2011. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0254.2011.00323.ten Web PDF Quote:"These results, six female Norse migrants and seven male person, should caution against bold that the great majority of Norse migrants were male, despite the other forms of prove suggesting the contrary."

- ^ G. Halsall, "The Viking presence in England? The burial evidence reconsidered" in D. One thousand. Hadley and J. Richards, eds, Cultures in Contact: Scandinavian Settlement in England in the Ninth and 10th Centuries (Brepols: Turnhout, 2000), pp. 259–76. ISBN two-503-50978-9.

- ^ Roger Highfield, "Vikings who chose a home in Shetland before a life of pillage", Telegraph, vii Apr 2005, accessed 12 Dec 2012

- ^ McEvoy, B.; Edwards, C. J. (August 2005). "Heredity – Human being migration: Reappraising the Viking Epitome". Heredity. 95 (2): 111–112. doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800695. PMID 15931243. S2CID 6564086. Retrieved Jun 7, 2020.

- ^ Alexander, Caroline (2011). Lost gilded of the Dark Ages : war, treasure, and the mystery of the Saxons. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. p. 188. ISBN978-i-4262-0884-iii. OCLC 773579888.

- ^ Keynes, Simon (1997). "The Vikings in England c. 790–1016". In Sawyer, Peter (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings. Oxford, UK: Oxford Academy Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN978-0-19-820526-5.

- ^ Magnusson, Magnus (1984). Lindisfarne: The Cradle Island. Stockfield, Northumberland: Oriel Press. p. 127. ISBN978-0-85362-210-9.

- ^ Kirby, D.P. (1992). The Primeval English Kings. London: Routledge. p. 175. ISBN978-0-415-09086-five.

- ^ Marking, Joshua J. (twenty March 2018). "Viking Raids in Great britain". Earth History Encyclopedia . Retrieved 2020-05-03 .

- ^ Historic England. "Raid on Jarrow 794 (1579441)". Research records (formerly PastScape) . Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ^ "ASC 794". Britannia Online. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

[...] the heathen armies spread devastation amid the Northumbrians, and plundered the monastery of Male monarch Everth at the mouth of the Habiliment. There, however, some of their leaders were slain; and some of their ships also were shattered to pieces by the violence of the atmospheric condition; many of the crew were drowned; and some, who escaped alive to the shore, were soon dispatched at the mouth of the river.

- ^ a b "Groundwork | SAGA - The Age of Vikings | Obsidian Portal". saga-the-age-of-vikings.obsidianportal.com . Retrieved 2020-05-03 .

- ^ Compare: Sawyer, Peter (2001) [1997]. "1: The historic period of the Vikings and earlier". In Sawyer, Peter (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings. Oxford Illustrated Histories. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 11. ISBN978-0192854346 . Retrieved 2017-01-eleven .

Several Viking leaders joined forces in the hope of winning condition and independence past conquering England, which then consisted of iv kingdoms. In 865 a fleet landed in East Anglia and was afterwards joined by others to class what a contemporary chronicler described, with good reason, as a 'great army'.

- ^ The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Manuscript B: Cotton Tiberius A.vi. Retrieved 12 September 2013. The entry for 867 refers to the Great Heathen Army: mycel hæþen here

- ^ Compare: Keynes, Simon (2001) [1997]. "3: The Vikings in England, c. 790–1016". In Sawyer, Peter (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings. Oxford Illustrated Histories. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 54. ISBN978-0192854346 . Retrieved 2017-01-11 .

The leaders announced to have included Ivar the Boneless and his blood brother Halfdan, sons of the legendary Ragnar Lothbrok, every bit well as another 'king' called Bagsecg, and several 'earls'; and if information technology is assumed that Ivar is the Imar who had been active in Republic of ireland in the late 850s and early 860s, it would appear that he had been able to meet up with his blood brother and assume articulation leadership of the regular army some time after its arrival in England.

- ^ Sawyer, Peter (2001). The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings (3rd ed.). Oxford: OUP. ISBN978-0-19-285434-half dozen. pp. 9–11, 53–54

- ^ Cannon, John (1997). The Oxford Companion to British History. Oxford: Oxford University Printing. p. 429. ISBN978-0-19-866176-4.

- ^ a b Sawyer, Peter (2001). The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings (third ed.). Oxford: OUP. p. 55. ISBN978-0-19-285434-half dozen.

- ^ a b Georgina R. Bowden, Patricia Balaresque, Turi Due east. King, Ziff Hansen, Andrew C. Lee, Giles Pergl-Wilson, Emma Hurley, Stephen J. Roberts, Patrick Waite, Judith Jesch, Abigail L. Jones, Mark G. Thomas, Stephen E. Harding, and Mark A. Jobling (2008). "Excavating Past Population Structures by Surname-Based Sampling: The Genetic Legacy of the Vikings in Northwest England". Molecular Biol Evol 25(2): 301–09.

- ^ Sawyer. The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings. p. 11

- ^ "Glossary of Scandinavian origins of place names in U.k.". Archived from the original on January 28, 2013.

- ^ Harding, Samuel Bannister; Hart, Albert Bushnell (1920). New Medieval and Modern History. Harvard University: American Book Visitor. pp. 49–l.

- ^ Montgomery, David Henry (2019). The Leading Facts of English History. Good Press.

- ^ "Treaty between Alfred and Guthrum". The British Library . Retrieved 2020-05-03 .

- ^ "Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum (AGu)". Early English Laws . Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ Sawyer, Peter (2001). The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings (tertiary ed.). Oxford: OUP. pp. 57–70. ISBN978-0-19-285434-6.

..in 944 Edmund drove Olaf Sihtricsson and Ragnald Guthfitson from York, and proceeded to reduce all of Northumbria to his rule..

- ^ "The Víking Era (793-~1100 CE)". gersey.tripod.com.

- ^ "UK Battlefields Resource Center - Britons, Saxons & Vikings - The Norman Conquest - The Boxing of Boxing of Stamford Bridge". www.battlefieldstrust.com.

- ^ a b c d Sawyer, Peter (2001). The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings (tertiary ed.). Oxford: OUP. pp. 17–18. ISBN978-0-19-285434-6.

It was however several years earlier he[William] had command of the whole kingdom...

- ^ John Cannon, ed. (2009). Sweyn Estrithsson: A Lexicon of British History. Oxford Academy Press. Oxford Reference Online. ISBN978-0199550371 . Retrieved nine July 2012.

- ^ Haywood, John (2016). Northmen: The Viking Saga Advert 793–1241. Macmillan. p. 269.

- ^ Forte, Angello (2005). Viking Empires. Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing. p. 216. ISBN978-0521829922.

- ^ "BBC - Scotland's History - Iona". www.bbc.co.uk . Retrieved 2020-05-03 .

- ^ a b c Archæologia Cambrensis: "Chronicle of the Princes", p. 15. Accessed 27 Feb 2013.

- ^ Harleian MS. 3859. Op. cit. Phillimore, Egerton. Y Cymmrodor 9 (1888), pp. 141–83. (in Latin)

- ^ The Annals of Wales (B text), p. 10.

- ^ The Chronicle of the Saxons. Op. cit. Archæologia Cambrensis, Vol. IX (1863), tertiary Ser.

- ^ Lavelle, Ryan (2010). Alfred'southward Wars Sources and Interpretations of Anglo-Saxon Warfare in the Viking Age. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydel Press. p. 23. ISBN978-one-84383-569-1.

- ^ Horspool. Why Alfred Burnt the Cakes. pp. 104–10

- ^ Welsh place names. Archived February twenty, 2006, at the Wayback Auto

- ^ "When the Vikings invaded Due north Wales". 2 April 2007. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ Holmes, Lilley, Claire, Keith. "Viking Swansea". Medieval Swansea . Retrieved 25 Jan 2022.

- ^

s:Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

s:Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. - ^ Forest, Michael (2005). In Search of the Night Ages. London: BBC. pp. 146–47. ISBN978-0-563-52276-8.

- ^ Andrea Dolfini; Rachel J. Crellin; Christian Horn; Marion Uckelmann (2018). Prehistoric Warfare and Violence: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. Springer. p. 349. ISBN978-3-319-78828-9.

- ^ Ó Corráin, Donnchadh (2001), "The Vikings in Republic of ireland", in Larsen, Anne-Christine (ed.), The Vikings in Republic of ireland. The Viking Transport Museum, p.19

- ^ Ó Cróinín, Dáibhí. Early on Medieval Ireland 400-1200. Taylor & Francis, 2016 . p.267

- ^ Ó Corráin, "The Vikings in Ireland", p. 28–29.

- ^ Ó Corráin, "The Vikings in Ireland", p.20.

- ^ Downham, Clare (2007). Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland: The Dynasty of Ívarr to A.D. 1014. Dunedin Bookish Press. p. 26. ISBN978-1-903765-89-0.

- ^ Ó Corráin, "The Vikings in Ireland", p.22.

- ^ Gorski, Richard. Roles of the Bounding main in Medieval England. Boydell Press, 2012 .p.149

- ^ Hudson, Benjamin T. "Sihtric (Sigtryggr Óláfsson, Sigtryggr Silkiskegg) (d. 1042)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:ten.1093/ref:odnb/25545. (Subscription or Uk public library membership required.)

- ^ Downham, Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland, pp. 51–52

- ^ Downham, Viking Kings of United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland and Ireland, p.61

- ^ Ridel, Elisabeth, Les Vikings et les mots; 50'apport de 50'ancien scandinave à la langue française, éditions Errance, 2009, p. 243.

- ^ Woods Breese, Lauren, The Persistence of Scandinavian Connections in Normandy in the Tenth and Early Eleventh Centuries, Viator, 8 (1977)

- ^ Ridel (E.), Deux marteaux de Thor découverts en Normandie in Patrice Lajoye, Mythes et légendes scandinaves en Normandie, OREP éditions, Cully, 2011, p. 17.

- ^ Cardon, T., en collaboration avec Moesgaard, J.-C., PROT (R.) et Schiesser, P., Revue Numismatique, vol. 164, 2008, p. 21–twoscore.

- ^ Curry, Anne (2002). The Hundred Years' War: 1337–1453. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. pp. 11–xviii. ISBN978-0-415-96863-8.

- ^ Vikingschat van Wieringen Archived 2011-07-18 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 26 June 2008. (Dutch only)

- ^ "O Barco Poveiro" – Octávio Lixa Filgueiras, 1ª edição 1966

- ^ Ann Christys, Vikings in the South (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), p. 65 and passim.

- ^ Kane, Njord (2015). The Vikings: The Story of a People. Spangenhelm Publishing. p. 32.

- ^ Ann Christys, Vikings in the South (London: Bloomsbury, 2015).

- ^ a b Ann Christys, Vikings in the Southward (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), p. 7.

- ^ "Digging up the 'Spanish Vikings'". University of Aberdeen. 2014. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ^ Ann Christys, Vikings in the South (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), pp. 5–12.

- ^ a b Haywood, John (2015). Northmen: The Viking Saga Ad 793–1241. Head of Zeus. p. 189.

- ^ Ann Christys, Vikings in the South (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), pp. 33–45.

- ^ Martínez Díez, Gonzalo (2007). Sancho III el Mayor Rey de Pamplona, Rex Ibericus (in Spanish). Madrid: Marcial Pons Historia. p. 25. ISBN978-84-96467-47-7.

- ^ Ann Christys, Vikings in the Southward (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), pp. 47–64.

- ^ Ann Christys, Vikings in the S (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), pp. 79–93.

- ^ Ann Christys, Vikings in the South (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), pp. 95–104.

- ^ Ann Christys, Vikings in the South (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), pp. 59–threescore.

- ^ a b Judith Jesch, Ships and Men in the Belatedly Viking Age: The Vocabulary of Runic Inscriptions and Skaldic Verse (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2001), p. 88.

- ^ Ullidtz, Per. 1016 The Danish Conquest of England. BoD – Books on Demand. p. 936.

- ^ Carr, John. Fighting Emperors of Byzantium. Pen and Sword. p. 177.

- ^ Colina, Paul. The Norman Commanders: Masters of Warfare 911–1135. Pen and Sword. p. 18.

- ^ Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, p. 217; Florence of Worcester, p. 145

- ^ Orkneyinga Saga, Anderson, Joseph, (Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas, 1873), FHL microfilm 253063., pp. 134, 139, 144–45, 149–51, 163, 193.

- ^ Translation based on Chibnall (ed.), Ecclesiastical History, vol. ii, pp. 203, 205.

- ^ Sturlason, Snorre. "Harald Hardrade" in Heimskringla, or the Lives of the Norse Kings. Trans. A.H. Smith. Dover Publications, Inc.: New York, 1990, p. 508, ISBN 0-486-26366-five.

- ^ Thunberg, Carl 50. (2011). Särkland och dess källmaterial. Göteborgs universitet. CLTS. ISBN 978-91-637-5727-3.

- ^ Blöndel, Sigfus. The Varangians of Byzantium. Trans. Benedikt Due south. Benedikz. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK. 2007, pp. 224–28, ISBN 978-0-521-21745-3.

- ^ a b Gabriel, Judith. "Among the Norse Tribes". 50.vi (November/December 1999 ed.). Saudi Aramco World. Archived from the original on 16 Jan 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ^ Ibn-Fadlan. Journey to Russia. Trans. Richard N. Erye. Markus Wiener Publishers: Princeton, NJ. 2005. ISBN 1-55876-365-1.

- ^ Jakobsson, Sverrir, The Varangians: In God's Holy Fire (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), ISBN 978-3-030-53796-8.

- ^ Roesdahl, Else; The Vikings: Edition 2, Penguin Group, 1999. p. 287

- ^ Thunberg, Carl L. (2010). Ingvarståget och dess monument. Göteborgs universitet. CLTS. ISBN 978-91-637-5724-2.

- ^ Title: Skálholt Map; Author: Sigurd Stefansson/Thord Thorláksson; Appointment: 1590 myoldmaps.com

- ^ Smith G. 1995. "Landna'yard: the settlement of Iceland in archaeological and historical perspective". Earth Archaeology 26:319–47.

- ^ Jr, Earle Rice (2009). The Life and Times of Erik the Blood-red. Mitchell Lane Publishers, Inc. ISBN978-1-61228-882-vi.

- ^ "half dozen Viking Leaders You Should Know – History Lists". History.com . Retrieved 2015-10-27 .

- ^ Diamond, J. Plummet: How Societies Choose to Neglect or Succeed (2005).

- ^ "History of Medieval Greenland". personal.utulsa.edu.

- ^ Diamond, Jared (July 17, 2003). "Why societies collapse". world wide web.abc.net.au.

- ^ Kuitems, Margot; Wallace, Birgitta L.; et al. (2021). "Evidence for European presence in the Americas in AD 1021" (PDF). Nature. 601 (7893): 388–391. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03972-8. PMC8770119. PMID 34671168.

- ^ Jones, Gwyn, A History of the Vikings (2d edition, Oxford, 2001).

- ^ "Vikings who chose a home in Shetland earlier a life of pillage".

- ^ a b c Helgason A, Sigurethardottir Due south, Nicholson J, Sykes B, Hill EW, Bradley DG, Bosnes Five, Gulcher JR, Ward R, Stefansson G. 2000. Estimating Scandinavian and Gaelic ancestry in the male person settlers of Iceland. Am J Hum Genet 67:697–717.

- ^ a b Goodacre S, Helgason A, Nicholson J, Southam Fifty, Ferguson L, Hickey E, Vega Eastward, Stefansson K, Ward R, Sykes B. 2005.Genetic show for a family-based Scandinavian settlement of Shetland and Orkney during the Viking periods. Heredity 95:129–35.

- ^ Helgason A, Lalueza-Fox C, Ghosh S, Sigurdardottir Due south, Sampietro ML, Gigli Due east, Baker A, Bertranpetit J, Arnadottir L, Thornorsteinsdottir U, Stefansson K. 2009. Sequences from first settlers reveal rapid evolution in Icelandic mtDNA pool. PLoS Genet v:e1000343

- ^ Lappalainen, T., Laitinen, V., Salmela, Eastward., Andersen, P., Huoponen, Thou., Savontaus, M.-L. and Lahermo, P. (2008). Migration Waves to the Baltic Sea Region. Annals of Human Genetics, 72: 337–48.

- ^ Moffat, Alistair; Wilson, James F. (2011). The Scots: a genetic journey. Birlinn. pp. 181–82, 192. ISBN 978-0-85790-020-iii

- ^ Starikovskaya EB, Sukernik RI, Derbeneva OA, Volodko NV, Ruiz-Pesini E, Torroni A, Brown MD, Lott MT, Hosseini SH, Huoponen K, Wallace DC. 2005. "Mitochondrial DNA diversity in ethnic populations of the southern extent of Siberia, and the origins of Native American haplogroups". Ann Hum Genet 69:67–89.

- ^ Tamm E, Kivisild T, Reidla Thou, Metspalu One thousand, Smith DG, Mulligan CJ, Bravi CM, Rickards O, Martinez-Labarga C, Khusnutdinova EK, Fedorova SA, Golubenko MV, Stepanov VA, Gubina MA, Zhadanov SI, Ossipova LP, Damba Fifty, Voevoda MI, Dipierri JE, Villems R, Malhi RS. 2007. "Beringian standstill and spread of Native American founders". PLoS One 2:e829.

- ^ Ebenesersdóttir, South. S., Sigurðsson, Á., Sánchez-Quinto, F., Lalueza-Fox, C., Stefánsson, K. and Helgason, A. (2011), "A new subclade of mtDNA haplogroup C1 found in icelanders: Testify of pre-columbian contact?" Am. J. Phys. Anthropol., 144: 92–99.

- ^ Ajioka RS, Jorde LB, Gruen JR et al. (1977). "Haplotype analysis of hemochromatosis: evaluation of dissimilar linkage-disequilibrium approaches and evolution of disease chromosomes". American Periodical of Human being Genetics 60: 1439–47.

- ^ Thomas W, Fullan A, Loeb DB, McClelland EE, Bacon BR, Wolff RK (1998). "A haplotype and linkage-disequilibrium analysis of the hereditary hemochromatosis factor region". Hum Genet 102: 517–25.

- ^ a b Milman N, Pedersen P (2003). "Evidence that the Cys282Tyr mutation of the HFE gene originated from a population in Southern Scandinavia and spread with the Vikings". Clinical Genetics 64: 36–47.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Viking_expansion

0 Response to "what problem may have caused the vikings to stop coming to north america"

Post a Comment